In the road-car world, vehicles that introduce revolutionary concepts normally spawn reams of imitators. They are the obvious progenitors of those that follow, laying down a clear lineage where you can track a certain style or engineering approach back through the years to its starting point. Even peaks of performance just become targets for others to beat, such as with the McLaren F1 in the ’90s and the Bugatti Veyron in the last decade. As long as it has seatbelts, lights and indicators, you can pretty much make what you like for the road. But in racing evolutionary terms, things are different. There are far more truly unique cars around.

Racing is a far more controlled environment – and has far more at stake. Here game changers have a bad reputation. They’re threatening. A danger to the show. Racers are rarely allowed to evolve to their ultimate potential before being culled; it’s like reverse Darwinism, where regulations deliberately excise the fittest to ensure the survival of the whole. Rule-makers are always trying to second guess car designers by imposing new limitations. Thankfully for us, engineers are a stunningly clever bunch, and this battle is what has led to some of the most breathtaking racing cars ever. How else would we have seen cars like the Brabham fan car, Tyrrell six-wheeler or Chaparral 2J?

Over the next couple of stories I’ll take a look at some of the cars that have changed the face of racing across a broad spectrum of competitions: single-seaters, sportscars and tourers. For the former, I’ll try not to be too gushing over the classic era of Lotus, the epitome of game-changer in Formula 1 terms. A disclaimer: this is also by no means meant to be a definitive list – just cars that I think had a big impact – so please do add your own ideas about game-changing cars in the comments. I’ve decided to split this piece across two loose themes, starting off with aerodynamics and concluding with power. Oh, the power!

It’s not always just individual cars that make the grade – there have been glory moments where a perfect storm of regulations, drivers and engineers come together to create purple patches: viz Group C/GTP sportscars, Group B rallying and CanAm to name three. For me, the former is a particular high, where sportscars were aerodynamic guided missiles that could out-run the best Formula 1 cars of the time. With the American IMSA GTP rules not having the same fuel-saving constraints as Group C, even more extreme aero packages were possible, producing planet-sized levels of downforce like on this Jaguar XJR-16. But as with any story, let’s start at the beginning.

1933 Napier-Railton

As the early decades of the 20th century passed, cars were becoming ubiquitous – the novelty was passing and a new phase of automotive use had arisen: the pursuit of speed. And once the pioneers of the day had their eye fixed on that goal, all the power and technology of the time swung into action. The mighty 2.7-mile Brooklands oval was constructed in 1907 to combat Britain’s draconian road regs of the period (a blanket 20mph speed limit across the whole country!) and cars were now being especially constructed to take advantage of its heavily banked course. This car stands out amongst all the competition, both in results and looks. The gleaming, tapering lines of the Napier-Railton barely contained the W12 24-litre aero engine that powered the car to 168mph – with only rear brakes available! Its 500bhp was delivered at just 2,200rpm. What I like about the Napier-Railton is that it’s ostensibly like a typical upright racer of the time – but one where its sheer speed has melted and raked back the bodywork with the force of its forward motion! It’s like a comic-book look of what fast should be. I think that even in contemporary terms this car looks as quick as it actually does go – and go it still does, as the car is kept in full working order at the Brooklands Museum.

1939 Auto Union Type C Streamliner

Auto Union and Mercedes represented the peak of pre-war Germanic racing know-how, crushing the period opposition with an assault of applied technology that the competition of the time couldn’t hope to match. Early attempts at data logging and aerodynamic profiling gained from aeroplane research resulted in this streamliner body: Bernd Rosermeyr took the 520hp, V16 car to over 400kph on a normal road in 1937 – just one of a run of 15 world speed records he broke in this car before his untimely death. This particular Type C is a replica created by Audi themselves from original plans to celebrate the centenary of the company.

1954-60 Maserati 250F

Could this be the first sign of appendages on racing cars that can actually be called wings? Rather than just profiling of the main body, the 250F featured small winglets just behind the front wheels. The small shape of big things to come.

1965 Chaparral 2A/1966 Chaparral 2E

By the mid-1960s, the art of aerodynamics was no new technology. Those pre-war land-speed record cars and the streamliner bodies applied to F1 cars of the ’50s at slipstreaming tracks like Reims had hinted at what was to come. Like Lotus in the UK (before, in fact), Jim Hall’s Chaparral team were at the forefront of utilising the new technology: the Chaparral 2 series of sportscars showed steady progress in turning something that had previously been guesswork into a science. The 2B sportscar of 1965 was the first serious competition car to utilise an inverted aerofoil wing. The 2C, with driver-controlled rear wing (predating DRS in modern F1 by a mere 45 years), 2D and 2E followed, competing at major racer like Le Mans and the Nurbürgring 1000km. Well ahead of F1, the 2E introduced side-mounted radiators and featured a ducted nose that created additional downforce, balancing out the power of the big rear wing – a wing whose angle was again driver-controlled via a foot pedal. Chaparral’s solid success with the system was countered by examples such as the car that follows: the structural failings of other teams’ attempts to master the approach led to high-wing technology as a whole being banned.

1968 Lotus 49B

Predictably, it took Colin Chapman to go one step further in applying aerodynamics to fragile F1 cars. Lotus’ first attempt was to bolt these teetering wings onto the successful Lotus 49. But what were they thinking?! This is the mid-term iteration of be-winged 49s: earlier versions featured a second high-level wing at the front as well. In retrospect it seems madness that they ever thought that the thin struts would survive the pressure that the wings generated: they didn’t of course, and near fatal accidents due to wing breakages meant the high wings were quickly abandoned in favour of tighter, smaller wings at the rear and on the nosecone.

1970 Lotus 72

Could 1970 be one of the most pivotal years in racing? Looking at the quintet of cars I’ve chosen from this year I’m tempted to say it is. From Formula 1 to sportscars to NASCAR (yes, NASCAR) aero was the only place to be from a development perspective. Just look at the progress: F1 cars hadn’t really changed their basic shape for 30 years, but now a radical shift occurred with cars like the Lotus 72 the result. Gone were the cigar-bodies; in are aggressive wedge shapes to cut through the air, balanced by sprouting, angular wings. The radiators moved to the sidepods after years of being nose-mounted and the engine gained an overhead intake: the layout of the modern F1 car was born.

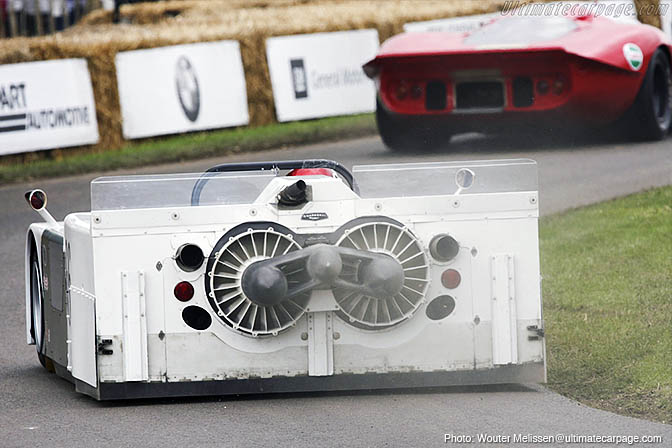

1970 Chaparral 2J Fan Car

The ultimate example of Chaparral’s expertise was the unique 1970 2J Fan Car: the boxy racer, shorn of exterior wings, used two 17″ fans at the rear to literally suck the car onto the track. As with moveable aero, the fan car was quickly banned. The McLaren team were at the forefront of the outcry against the car, claiming the 2J would kill CanAm by dominating it – which was rather cheeky as that’s exactly what McLaren had been doing since 1967…

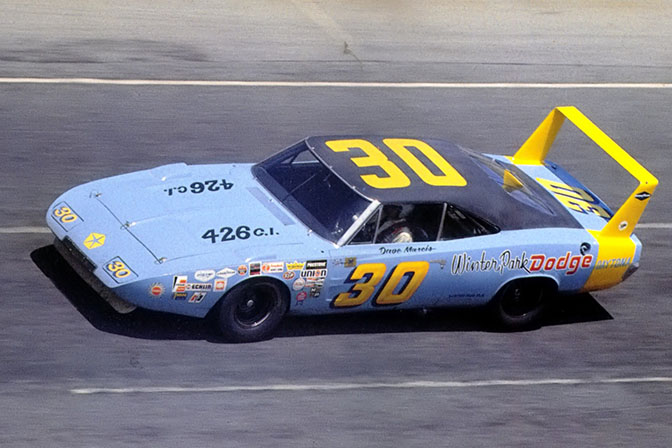

1970 Dodge Charger Daytona

A wind tunnel in NASCAR? Computer analysis? What the?! But yes, a pointed nosecone was bolted to the blunt nose of the Charger and the rear wing set high to be in cleaner airflow to create this radical look for NASCAR in 1970. To qualify for their NASCAR entry, the Dodge peppered their forecourts with road-going versions as well, making salesman have to deal with a Jetsons vs Flintstones mix of cars.

The extreme looks of the Charger and similar Plymouth Superbird were given short-shrift by the rule makers: NASCAR countered any of this new-fangled aero nonsense by mandating restricted engine power and throwing weight at them, rendering the Winged Warriors impotent by the end of the season. Not only that, but they stayed firmly on the forecourts and not in the hands of punters, who at the time just couldn’t get with these cars’ extreme looks. Back to power over physics.

1970 CanAm McLaren M8D

Over in North America the CanAm series was in full swing. One of the only series where anything – and for once that term was quite literal – went, CanAm is still a name that makes race-fans weep with joy. The M8 series saw a full aerodynamically efficient wedge-shape employed in attempt to tame the brutal power available: Denny Hulme swept the 1970 and 1971 championships, with all but one race victory going to McLaren in ’70 and all but two in ’71.

1970 Porsche 917

Curvaceous sports racers festooned the grids of the late ’60s and early ’70s, but the Porsche 917 is the defining car of that generation. With its perfect looks and tapering lines, the entire car was optimised around weight saving and the big mid-mounted 550hp engine introduced many exotic metals which would become synonymous with racing: titanium, magnesium and specialised alloys. On the car’s introduction in 1969 its low-drag characteristic, combined with the powerful engine, made the 917 far faster than anything else competing at Le Mans at the time – but massively unstable. Developments in aero understanding ahead of the 1970 season increased downforce with the classic short-tail, wedge-shaped, flared rear bodywork and the 917’s place in the history books was assured.

Finally Porsche could lay claim to Le Mans, a prize they’d been chasing since 1953. The 917 also heralded a brand new era of racing: that of the mass customer car programme. With Porsche ready and willing to sell privateers a car that was almost guaranteed to be in with a chance of winning, 917 variants dominated grids in the early ’70s, something they would go on to do again in the ’80s.

1975 Lancia Stratos

The Stratos was like a UFO amongst contemporary rally cars: a big wrap-around screen to maximise visibility with virtually no rear view (after all, who’s coming up behind you on a rally stage?), a no-frills wedge-shape and kicked-up tail threatened total domination of the retro competitors – and promptly delivered it. A singing Ferrari Dino engine did the Stratos’ iconic status no harm.

1977 Lotus 78

A technical arms race rapidly developed in Formula 1 during the ’70s, with Lotus at the forefront of introducing new concepts – sometimes before they were ready… The 78 was the car that introduced the concept of aerodynamic ground effect and began a cycle of almost annual car updates in F1 . Remember that the previous Lotus, the 72, had been in service for almost seven years…

Wind tunnels and rolling roads were now typical weapons in an F1 team’s arsenal: the low-drag 78 used full-length skirts along its large sidepods (which featured inverted-aerofoil underside profiles) along with the downforce from its wings to produce unheard-of levels of downforce – over 2,000 pounds at speed. The revised model, the Lotus 79 in 1978, rectified the reliability problems of the 78 and delivered total domination.

1978 Brabham BT46B Fan Car

The BT46 developed the Chaparral’s 2J concept to a new level: a single huge fan was combined with full ground-effect principles of air-sealing skirts and sidepods to produce another huge leap forward in levels of downforce – despite the team initially claiming that the fan was “for cooling purposes”. No one was fooled. The car raced once only, dominating the Swedish Grand Prix – and was then withdrawn by Brabham in the face of an imminent ban.

1981 Lotus 88

For the 1981 season Lotus introduced yet another new concept to F1 racing: the twin-chassis. The 88 was a car within a car: with moveable skirts now banned by the FIA, Lotus mounted the cockpit on an internal chassis independently sprung from an outer ground-effect chassis. This outer part was effectively one big wing in an effort to both further increase the downforce available and reduce the resulting fatigue this caused drivers. As with the McLaren MP4/1 it was also constructed from carbon fibre, a material only just being applied to racing purposes. The difference was that the 88 was protested almost as soon as the car was being rolled into scrutineering for the first race of the season, and banned for good by the middle of the season without having taken a race start.

1982-1985 Porsche 956

The 956 heralded the start of another period of Porsche domination – both from the factory and a fleet of privateers not just buying off-the-shelf cars but also pushing forward their development, just as they had with the 917. Six wins in a row at the Le Mans 24 hours was kicked off by victory for the factory team in 1982 (which in itself followed a win for a 936 in 1981). A flat bottom was matched to a set of venturis to make it the first Porsche to use ground-effect aero: that and the flowing lines of the lightweight, kevlar-reinforced fibreglass body and big rear wing provided three times as much downforce as a 917. And this was a car built to regulations designed to end Porsche’s domination of sportscar racing!

1986-97 Porsche 962

The initial 962 was superficially a minor update to the preceding 956: a slightly longer wheelbase to suit IMSA regs, a new chassis, roll-cage and KKK turbo-charged flat-6 2.8-litre engine being the major changes. But the 962 was all about the tuners.

Like the 935, the 962 provided the platform for a plethora of privateer variants: aero changes included everything from adding a simple nose winglet to completely redesigning the entire aero package. Teams like Richard Lloyd Racing (with the 962GTI shown here), Dauer, Kremer and Brun all built and sold highly-modified 962s. A sign of the 962 chassis’ excellence was the fact that it was still competing in – and winning – races over a decade later.

1991-2 Williams FW14/B

The FW14B still remains the pinnacle of Formula 1 technology. The arrival of design superstar Adrian Newey at the English team in combination with a relative free period for Formula 1 regulations (or maybe more accurately the rule-makers hadn’t completely understood just what the teams were thinking of) led to the creation of the most sophisticated car to run in F1. It was an electronics marvel: active suspension, traction control, semi-automatic gears and anti-lock brakes mated to the powerful Renault V10 and cutting-edge aero meant the FW14B was head and shoulders above the competition. They didn’t stand a chance. With its development refined over the 1991 season, the B spec utterly crushed the opposition in 1992. The result? Williams’ plethora of technology was added to that growing shelf at the FIA marked: Dangerous. Do Not Allow In The Wild.

2012 DeltaWing

Bodies like the FIA now take pains to try and avoid allowing teams to come out with massive advantages, so the big breakthroughs have been lessened in the recent decade, if not eradicated. Cars have dominated, for sure, but often by making best use of the rules there are rather than utilising new development paths. Major changes in rules packages are usually the only time that loopholes can be exploited, but again they’re soon stamped on: think mass damper, double-diffuser, F-duct and so on.

So is the day of the game-changer over? Not necessarily. Hybrids and electric racers are not just inevitable but already here: and the best news is that they are just as fast and furious as ever – and introduce brand new concepts to exploit. And can they get much more out-there than the DeltaWing? Its rocketship shape is devoid of wings – downforce is generated by the underbody – the chassis is super lightweight, weighing in at just 475kg, and power comes from a small 1.6-litre turbo unit. It’s taken the special 56th slot at this year’s running of the Le Mans 24 Hours – and I for one am really looking forward to seeing how it performs. What’s crazy today is so often genius tomorrow…

Jonathan Moore

Photos copyright their respective owners

would be interesting to see the "fans" taken up in a super lap car, go on someone, do it!

This is the most mouth watering post ever! Go 2J and 917!

787B was a game changer for sure. It displayed the importance of power to weight (especially in engines) and reliability. The R26b itself was a marvelous piece of technology. That infinitely variable intake is just genius.

The most frustrating one of these cars had to have been the Williams F1 car. Ayrton Senna's skill was no match for these technological marvels so he decided to join Williams the following year, and then they were banned. He was left with an unpredictable car that ultimately led to his demise. Such a shame.

I think the Audi Quattro should be added as well. Making the difference with 4WD. Thanks for this post though, excellent stuff to read!

Awesome write up Jonathan. Loved every word of it!!

What a great history leason, thanks Mr Speedhunter!

The "winglets" on the Maserati 250F were there just to prevent water from flying up into the drivers view from the front wheels when it was raining. They dont have any aerodynamic benefits.

dang those fan cars look awesome... the Porsche's are nice too..

essracing-vmfracing.weebly.com

Dean, was thinking that myself!!

Great write up!

this post is RIDICULOUSLY EXCELLENT. Keep it coming Mr. Moore, this in depth game changer of motorsport is fascinating.

I'm a mad car racing nut and even I learned something new here!

Great article, more of that please.

Wow, some great pics of some insane race cars, good post.

Fantastic post Moore. An addition to the pic of the Maserati 250f however, the little "wing" behind the front wheel was to actually protect the drivers face from debris being flung up by the front wheels.

Exellent article!! I've always thought the Williams FW15 was the better active car. It had the same electronics as the FW14 but the FW15 was packaged better. It is sort of depressing that F1 will never again have such great leaps in technology as the F1 cars featured in this article.

Deltawing @ LeMans? That thing doesn't look like it could turn.

Can't believe the Red Bull X2010 and X2011 weren't mentioned.

Fantasy cars of course, but so is the Deltawing.

The wings on the Daytonas and Superbirds were that high so the trunk could still be opened.

@ All

Ah yes, the 250F that was a bit of a cheeky inclusion. I should have left it as I originally phrased it, which was that they *looked* like wings rather than actually being wings!

@ 2jz

I do love the 787, but I'm not sure it was a game-changer. Very interesting for sure, but not something that kick-started a whole new successful concept and it did effectively luck into its LM win...

@ Chris

Quattro power in part 2!

Good post. However I would argue that Ground Effect is a bad idea, so is the idea of sucking the car to the road, and movable skirts.

The reason? The moment the car lifts off the track slightly, the majority of down-force is lost, resulting in an airborne car and a catastrophic accident. This is one regulatory ban that was brought in for sensible reasons.

Great article, shame you left out 7/8 scale cars though! Cars like Smokey Yunick's Camaro and Bill Elliot's #9 Thunderbird that dominated the super speedways did so by running bodies that were roughly 7/8 the scale of everyone else--less overall frontal area and less drag! Thanks to them, body templates are the norm in stockcar racing.

Great article, a couple I'd add:

Audi Quattro: quite obvious

Renault RS01: first turbo F1

Toyota Eagle MkIII: perhaps the ultimate Group C/GTP car, nearly 10 000 kgs of downforce and the first car to introduce front diffusers to sportscar prototypes as we know them. Dominated IMSA GTP in '92 and '93.

ST185 WRC Celica: Although the modern antilag system was first tested by Quattro S1 in the 80s, Toyota were the first to perfect the antilag system to be reliable enough for rallying.

Fantastic insight, and I love hearing about the past successes of racing. It's also awesome to note that Porsche is seemingly one of the most successful racing establishments of this post, and also somewhat understated compared to the other big brands of racing. I can't wait to see what this season brings about!

The Williams FW-15 is far more technologically advanced than the FW-14B, it still remains the most technologically advanced Formula 1 car made to date, thats why those two cars where unbeatable in 1993 and so then banned at the end of the season, the active suspension kept the car at a constant hight of 6cm from the track regardless of circumstances, it was the pinnacle of Formula 1 technology. and a true game changer because after they where banned they thought of new areas to use the computers that powered all the electronics in that car.

This post was very good to read. Thanks!

I love all the inventions the Chaparrals come out with.. They are like mad scientists that come out with genius ways to win but the "heros" always have to come in and ruin the fun

Where the FWING?

great article.

porsches and chapparals

great post!! can anyone tell what that red car is infront the chapparal fan car from the 2nd picture...thanks in advance!

AHxDe2 Im obliged for the blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Want more.

ozFS5v This article is for professionals..!

As usual Jonathan Moore delivers an excellent article!

So the delta wing, a car that has turned not a single lap in competition gets the nod but no mention of the quattro or 911 GT3 H?

When I first saw the long, aerodynamic shape of the DeltaWing race car, I assumed it was built for the salt of Bonneville. That's not the case though, as the Nissan-supported DeltaWing is bound for Le Mans, where it's scheduled to run this year

Never seen this type of work looks like professional racing to victory

Ford F3L a.k.a. Ford P68

Just wanted to say that I read your blog quite frequently and I’m always amazed at some of the stuff people post here. But keep up the good work, it’s always interesting. See ya,

http://chaosfaction2play.com http://super-mechs.com